Introduction

This online resource provides an overview of best practices and recommendations in media literacy educator training. This resource is designed for our communities of educators, stakeholders, and policy developers as well as anyone else interested in the field of media and convergence literacy education.

The work here is inspired by the research and outcomes of the Media in Action project who work directly with teachers, librarians, teacher trainers and other educators.

Why Digital Storytelling in media and news literacy?

Sustainable Future

COUNTRY CONTEXT

Good practices of MIA in Partner Countries

Collating resources

There are a lot of resources to choose from and it can be daunting knowing where to start. We focussed our search initially by looking at the European Digital Competency framework for educators DigCompEdu We then looked at the 6Ws of Journalism and applied this method of Who, What, When, Where, Why and How questioning to the sections of the framework relating to problem-solving and content creation. The 7Ws of Media and Information literacy were elaborated and resources were proposed for each section and subsection. The team collected all of the suggested resources as a spreadsheet before testing each one out, checking the copyrights, and agreeing which should be included. We felt it important to include resources from across Europe so favoured resources which could be interpreted by on-screen translation tools.

Resource Bank

We wanted the bank of resources to look good as well as be easy to update. After testing a few plugins Elementor was chosen. It allows WordPress posts and pages to be turned into interactive, clickable and collapsible sections improving readability and usability.

Creating resources

Anyone can create a MIA account and upload their own resources. Once approved by a member of the MIA team, resources are made public or added to the resource bank. In this way we hope to showcase examples of digital storytelling content created in educational contexts.

Digital Storytelling

The resource bank includes an extensive list of digital storytelling tools. We use Twitter to crowdsource further examples and regularly update the list to check all the tools are still working.

Training educators

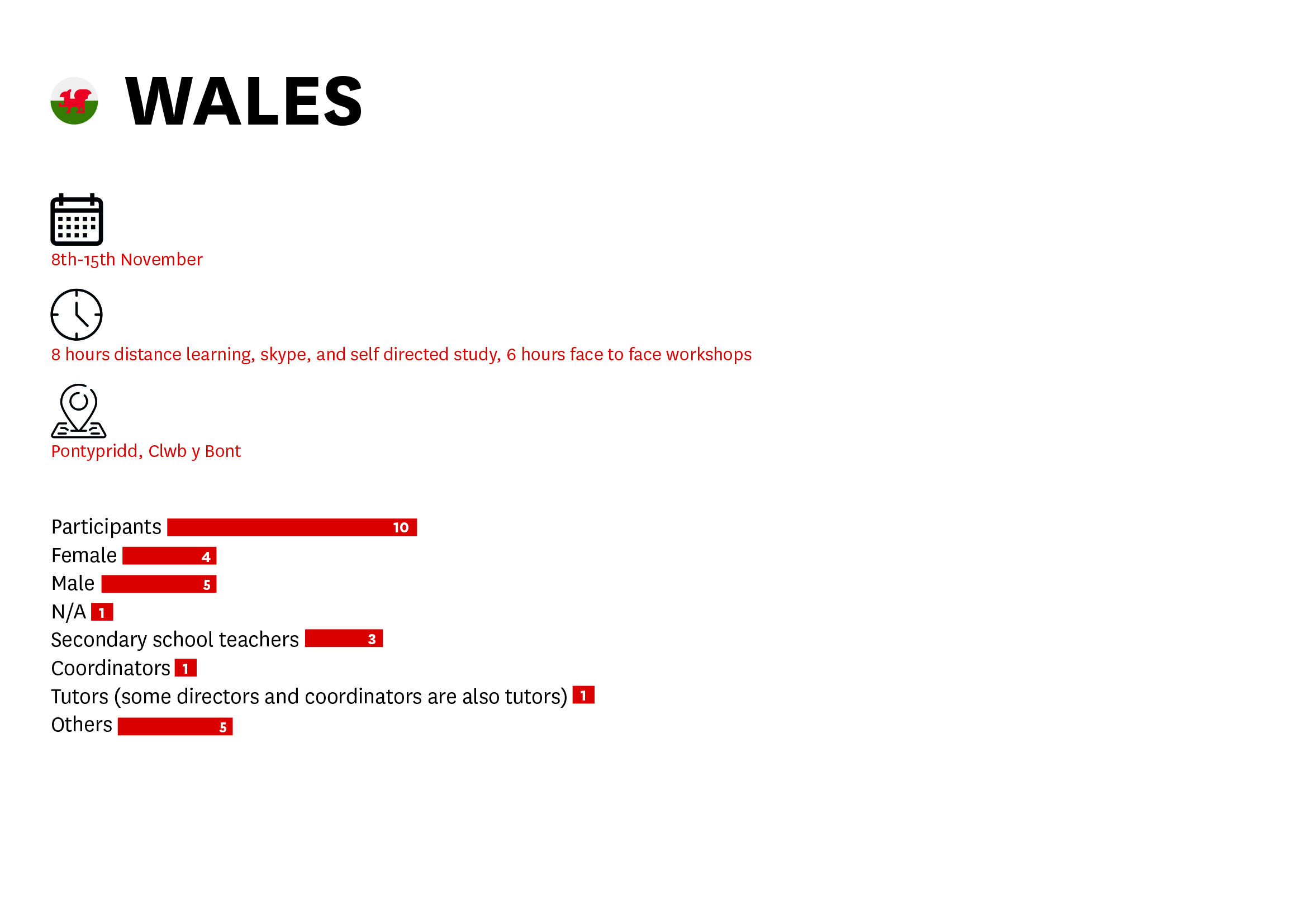

For the workshops in the UK we have arranged a flexible and blended approach, partially webinar and Skype based online training and partially face to face workshop. This is because the time available for educator CPD is limited and tends to be booked up early. It was also necessary to emphasise the digital competencies over the media literacy aspects; educators were more receptive to this than to being trained in media literacy, possibly because of the emphasis placed on digital skills.

Reaching out

MIA has created and strengthened links with the wider community by social media interaction and by conference attendance. Good practices in the UK included joining a workshop in Mozilla Fest’s MisInfoCon and subsequent communication with fellow participants to disseminate MIA’s resources and also to plan the co-creation of new resources. We have also created and maintained close links with other projects, MIA will be included in the TaccleCPD project as an example of teacher education in embedding ICT across the curriculum.

Accordion Content

Accordion Content

Good practices of MIA in Portugal

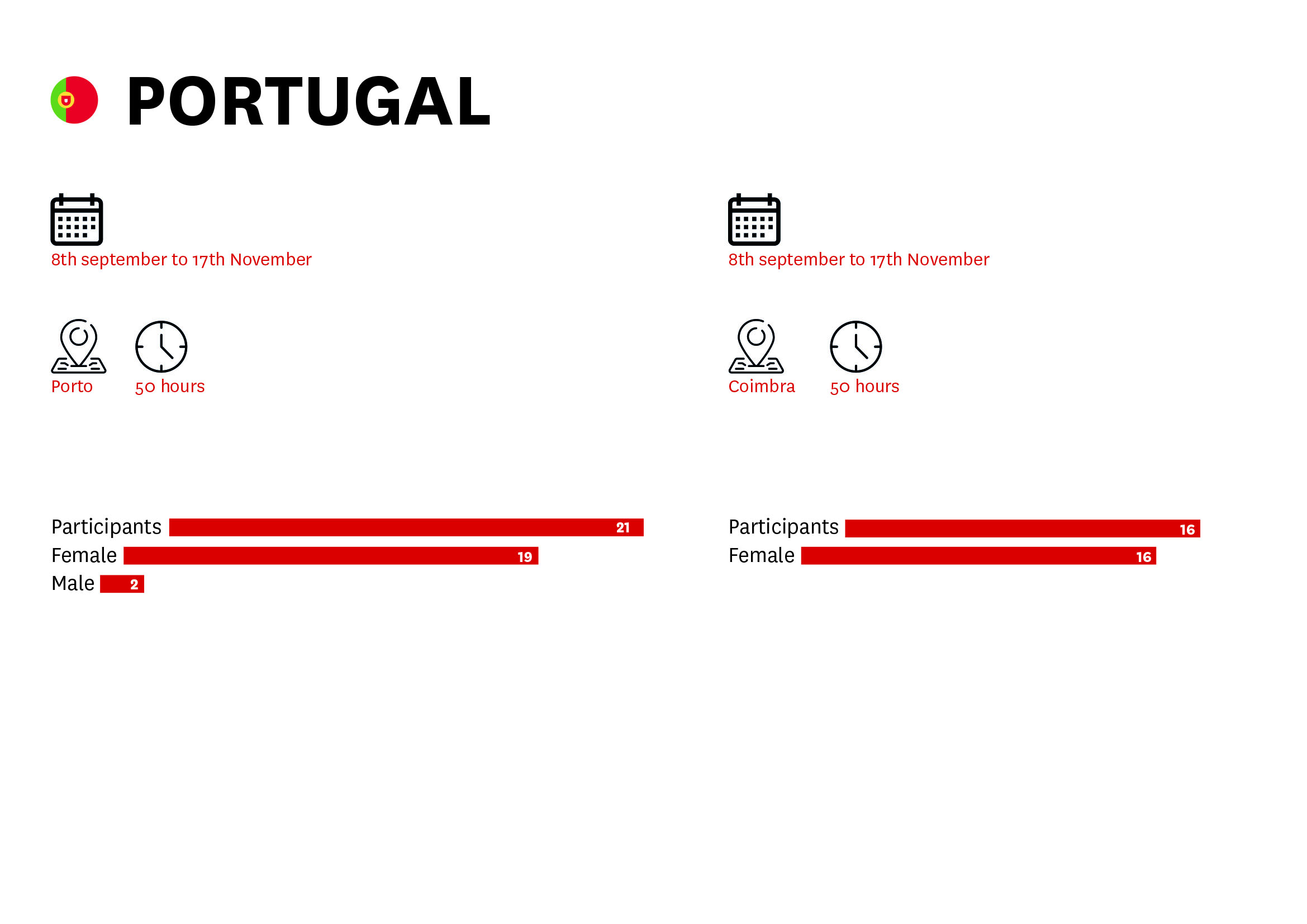

In Portugal, apart from the emphasis on dissemination, we would consider that our best practices are related to the work done on the training for teachers and school librarian teachers. We consider that we have worked on a two-level basis. At first, the European level, since we have followed the content strategy that was approved in Wales in the kick-off meeting, regarding the content structure and also theoretical and practical approaches. Secondly, the national level. The Portuguese regulation for teaches training has some particularities, such as a national agency (CCPFP- Conselho Científico-Pedagógico da Formação Contínua) that evaluates the teachers training and decides if the training is good enough to be accredited. Moreover, implicitly, teachers will only find relevant training that has accreditation. This means that in Portugal we needed to do this to have a really motivating training to teachers. This was a very tough phase because we needed to create the basis of the training in a very short time in order to submit and acquire the accreditation.

At the same time we were discussing with other European partners, we were also having intense communication in Portugal with the Ministry of education, the School libraries network and the National Plan for Reading (PNL2027), that were very interested in what we were proposing and became our close partners in Portugal. These are the most relevant organizations in Portugal in the field of media literacy and they work close with teachers and already made e previous diagnostics where they consider Media and civic education very important for teacher training. At this national level, is also important to say that the Ministry of Education clearly suggested us how important could be that we could deliver the training in a way where the trainees could be prepared to train other colleagues in the future. We consider that this is a very good way of approaching training: training trainers.

The amount of hours of the training were guaranteed with the 3 Portuguese partners, that clearly considered that since this a so relevant training area it would be significant that we could deliver 50 hours of training (25h theoretical and practical and 25h practical work of the teachers with their students at school). In the final stage of the 50h, there is an evaluation. This training can be replicated in the future.

This initiative is aligned with the areas of lifelong education and with the broader area of Communication Sciences, which includes the specificities of journalism, citizenship education, and digital education. It aims to reinforce the knowledge teachers have on the intrinsic connection between media education and citizenship, using practices and dynamics, which involve the media as learning tools. The proposal stems from the identification of gaps at the level of media education and citizenship education connected with the use of digital media and which need to be bridged. The core idea of the initiative is to contribute to train teachers in the field of media education and citizenship education, with a special focus on the digital. This training encompasses a two-fold meaning: on the one hand, it aims to foster and stimulate the possibility of target teachers themselves becoming multipliers and trainers among their peers after the being trained; and, on the other hand, foster an improved application of the acquired knowledge in their own activities and teaching planning with students, thus reinforcing the students’ own knowledge.

In recent years, the importance of training and fostering the existence of citizens capable of critically and contextually putting into practice the media and the new technologies in particular has assumed greater emphasis and is considered to be a public necessity (Referencial De Educação Para Os Media, 2014). The GDE, through the services of the Educational Resources and Technologies Team – ERTT, the Network of School Libraries, and the National Reading Plan have concentrated their efforts into reinforcing teachers’ competencies in this area. The need to focus on this field of media education has been identified, for instance, in the successive evaluations of the application of the benchmark Aprender com a Biblioteca Escolar (AcBE) (2013-14; 2014-15; 2015-16). Moreover, the guidelines and suggestions of the Referencial de Educação para os Media are also crucial, as it points to the need to expand media literacy in schools, in an in-depth and interdisciplinary way, in mandatory schooling, in line with what Vítor Tomé (2016) advocates. One of the literacies considered a priority by the Plano Nacional de Leitura 2027 is precisely digital literacy.

Boas práticas MIA em Portugal

Em Portugal, à parte da disseminação, podemos considerar que as nossas melhores práticas se relacionam com a formação de professores. Neste campo, trabalhamos em dois níveis. Primeiro, o Europeu, uma vez que seguimos uma estratégia de conteúdos que foram aprovados na reunião inicial em Gales, no que respeita ao conteúdo e à estrutura. Em segundo lugar, a nível nacional. A regulação Portuguesa tem particularidades a ter em consideração, como as definidas pelo CCPFP – Conselho Científico-Pedagógico da Formação Contínua, que avalia a formação de professores e só credita a que considera relevante. Isto significa que em Portugal precisamos de passar por este processos para ter uma formação que motive os professores. Esta foi uma fase dura de ultrapassar, uma vez que tivemos de criar as bases da formação num curto período de tempo para submeter e conseguir a creditação.

Ao mesmo tempo que debatíamos com os parceiros Europeus, estávamos a desenvolver uma comunicação intensa em Portugal com o Ministério da Educação, a Rede de Bibliotecas Escolares e o PNL2027, que estavam interessados nas propostas. Estas são as mais relevantes organizações na área em Portugal que trabalham de forma muito próxima com professores, considerando que a educação cívica e mediática é muito relevante na formação de professores. A nível nacional é também importante anotar que o Ministério da Educação sugeriu oportunamente que esta formação poderia ter uma componente de formação de formadores, ou seja, de formação de professores que pudessem ser futuros formadores.

O número de horas de formação foram determinadas em conjunto com os três parceiros nacionais, que consideraram que a falta de formação na área poderia implicar 50 horas de formação (25h teóricas e 25h práticas). No final das 50h, é feita avaliação. Esta formação pode ser replicada no futuro.

Esta ação está alinhada com as áreas de formação contínua e com a grande área das Ciências da Comunicação, incluindo nesse âmbito as especificidades do jornalismo, da educação para a cidadania e do digital. Pretende reforçar o conhecimento que os professores têm sobre a ligação intrínseca entre a educação para os media e a cidadania, usando práticas e dinâmicas que implicam os media como ferramentas educativas. A proposta parte da identificação de lacunas que se verificam ao nível da educação para os media e educação para a cidadania ligadas ao uso do digital e que podem ser potenciadas. A ideia central da ação é contribuir para a formação de professores na área da educação para os media e para cidadania, com especial enfoque no digital. Esta formação tem um duplo sentido: por um lado pretende potenciar e estimular a possibilidade dos professores alvos da formação serem, eles próprios, multiplicadores e formadores entres os seus pares após a formação e, por outro, potenciar uma melhor aplicação dos conhecimentos adquiridos nas suas atividades e planificações letivas com os alunos, reforçando, por este meio, os conhecimentos dos próprios alunos.

Nos anos mais recentes, a importância de formar e potenciar a existência de cidadãos capazes de operacionalizar de forma crítica e contextual os media e as novas tecnologias em particular conquistou maior preponderância e assume-se como uma necessidade pública (Referencial De Educação Para Os Media, 2014). A DGE, através dos serviços da Equipa de Recursos e Tecnologias Educativas – ERTE, a Rede de Bibliotecas Escolares e o Plano Nacional de Leitura têm concentrado esforços em reforçar as competências dos professores neste âmbito. A necessidade de apostar nesta área da educação para os media é, por exemplo, identificada nas sucessivas avaliações da aplicação do Referencial Aprender com a Biblioteca Escolar (AcBE) (2013-14; 2014-15; 2015-16). Além disso, são também fundamentais as diretrizes e sugestões do Referencial de Educação para os Media, que aponta para a necessidade de aprofundar a literacia para os media na escola, de forma aprofundada e interdisciplinar, no ensino obrigatório. Uma das literacias apontadas como prioritárias pelo Plano Nacional de Leitura 2027 é precisamente a literacia digital.

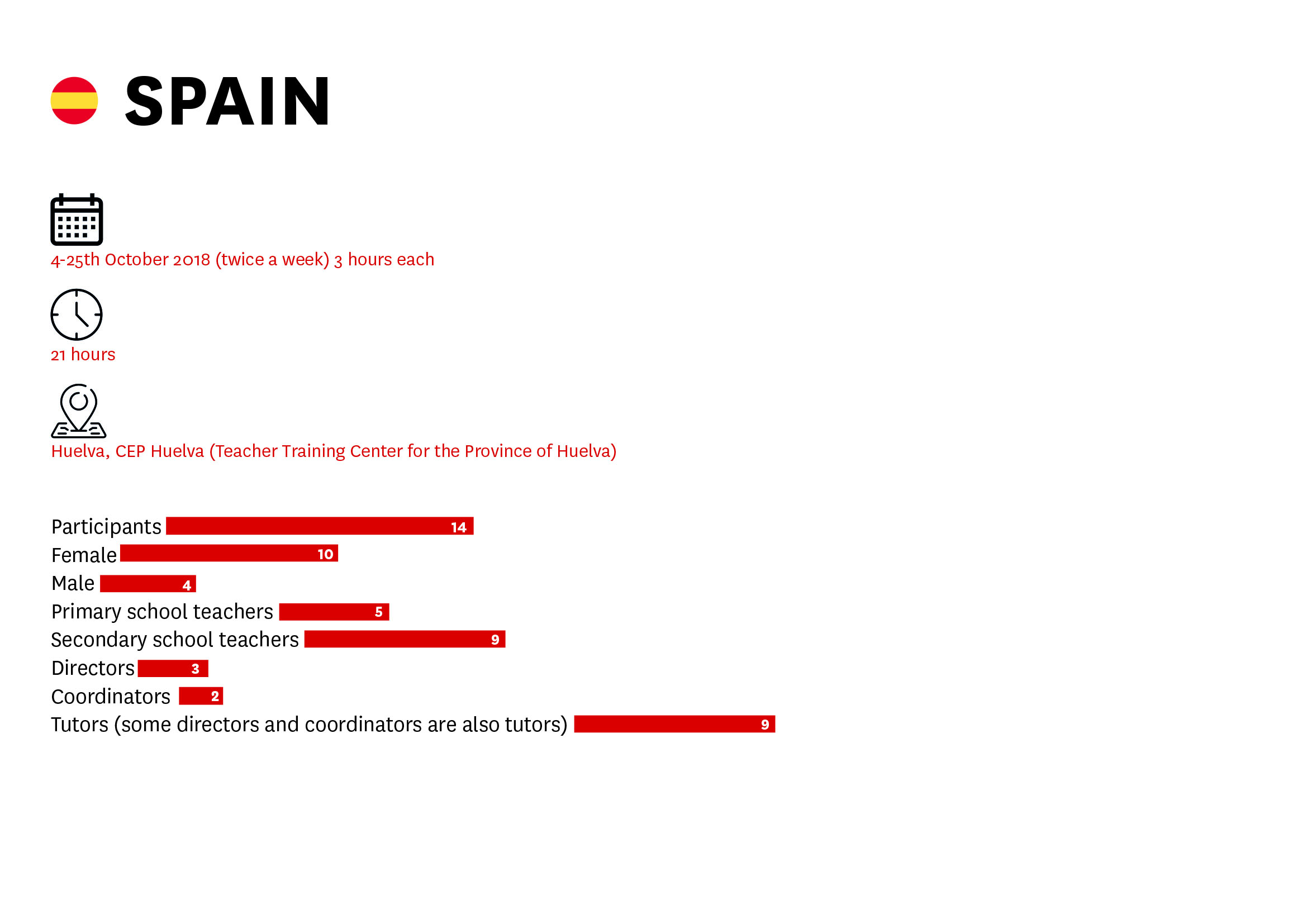

In Spain, the course was completed in 21 hours of face-to-face training spread across the month of October in bi-weekly three-hour sessions, on Tuesdays and Thursdays. We were able to offer the course through the Center for Teaching in the Province of Huelva (the government entity responsible for offering professional development to public school teachers) and we had a total of 14 participants. The diverse group included primary, secondary and vocational training teachers and administrators, with varying levels of media literacy and technological skills.

The design of the lessons called for the use of innovative resources to teach theoretical content and generating debate and participation in our educators. We also provided materials and guidelines that could be used directly in the classroom. In many cases teachers took some of our materials (the storyboard for example) and used it in their classroom the next day.

We began by giving participants an overview of the project, the 7Ws design and structure and highlighting the importance of asking questions as part of the process to become informed, media literate citizens. We showed participants the repository of resources, and the types of resources they can expect to find there as well as the process to upload their own tools and materials to the repository.

Throughout the course, we highlighted the importance of the digital storytelling format as a powerful method to connect with students and a way to counter current issues related to the use of media. We pinpointed journalistic storytelling as an especially effective method due to the nature of the current media environment with issues such as disinformation, clickbait, astroturf, among others. We specified different methods of data manipulation that affect citizen perception and ultimately public opinion on important issues.

One of the main limitations we encountered was the unreliable connectivity and other technological limitations at the centre. On one occasion we were unable to access the Internet and on another day, laptops were not completely charged and we were forced to rethink the final part of the lesson due to this issue. Rather than becoming frustrated, we took these situations as teaching opportunities, since teachers are faced with these types of problems daily and we discussed the importance of always having an alternate lesson plan. We planned highly technological lessons and backup plans for no technology scenarios.

We relied on different types of graphic organizers (to promote our participants’ thinking, brainstorming and planning skills) including some specific to storytelling such as storyboards and podcast planners as well as others that connected the storytelling techniques to specific academic goals and evaluation techniques. We also sent assignments home in cases where it was important to have a computer or Internet access.

We put in practice the use of a variety of mobile phone apps to achieve our didactic goals regardless of Internet connectivity or laptop availability, and even though we encountered some limitations such as low memory, battery or an older software version, it was very successful. As the course program progressed, we communicated with teachers before class to download the required apps and we would be ready to go at class time.

We foresaw resources in English as a limitation for our educators but we were able to tackle this issue by teaching them how to use Google Chrome to automatically translate all the websites. As a result, lessons using English language resources went seamlessly and were highly successful.

Teachers were proactive and actively participated in every activity; in most cases they worked in groups and adapted the activities to their students and their context. Our participants’ interest in the instrumental aspect of the course was high but we evidenced a significant interest in the media literacy topics, especially copyright, fake news and disinformation, online safety and prosumption. We believe that the combination of instrumental digital storytelling skills and the development of an awareness of media literacy issues was fruitful and provided an opportunity for significant learning to take place. In many cases, teachers connected what they were learning to programs that were already in place at their schools and were able to improve them and enrich them by adding new components from our lessons.

We made a point of including materials that were accessible, free and easy to use by any teacher. We also included resources that were tailored to the subject and context of each of our teachers; for example, we had a Maths teacher who was able to use digital storytelling in her classroom by using a Flipped Classroom tool and a video from the TEDEd platform to teach how graphs and statistics can be misleading. We accompanied her in every step of the process and problem-solved all her issues (for example, she wanted to slow down the speed of the video and we taught her how to do that) until she successfully created her lesson including the video and a hyperlinked text including other contents.

Another one of our participants was a very innovative vocational training teacher and taught health in a sanitary education program. He is currently designing a gamified yearlong program resembling MasterChef to teach about nutrition, and used several of the tools he learned from us to create unique materials for his students. The topic of misleading news and disinformation in scientific reporting was especially interesting to him and he gave important examples from his subject and his context. This was very enriching as other less media literate participants evidenced how this is an all-encompassing topic that affects every subject. He will also send us an update of his program for the first trimester, which ends in December.

We believe that having the course spread over 4 weeks was advantageous because the interest displayed by several of the teachers offered us opportunities to adapt the course to their needs and follow up on their specific situations. At the end they were all committed as media literacy educators with the necessary tools to include these topics in their classroom at some level. They also left with an instrumental toolkit to be implemented in their school communities at varying levels.

Proyecto MIA en España

Nuestro curso se desarrolló en 21 horas de formación presencial repartidas a lo largo del mes de octubre en sesiones bisemanales de tres horas, los martes y jueves. El curso se impartió con la colaboración del Centro del Profesorado de la Provincia de Huelva (la entidad gubernamental encargada de ofrecer desarrollo profesional a los profesores de las escuelas públicas) y en su sede. En total fueron 14 participantes que conformaron un grupo diverso que incluía a profesores y directivos de centros de primaria, secundaria y formación profesional, con distintos niveles de competencia mediática y habilidades tecnológicas.

El diseño de nuestras clases requería el uso de recursos innovadores para la enseñanza de contenidos teóricos y que generasen debate y participación en nuestros educadores. Del mismo modo, proporcionamos materiales y directrices que ellos mismos podrían utilizar directamente en sus aulas. En muchos casos, los educadores utilizaron algunos de nuestros materiales (por ejemplo, el guión gráfico) y los utilizaron en sus clases al día siguiente.

Comenzamos dando a los participantes una visión general del proyecto, el diseño y la estructura de las 7Ws y destacando la importancia de hacer preguntas como parte del proceso de convertirse en ciudadanos informados y mediáticamente competentes. Del mismo modo, se les presentó el repositorio de recursos (OERS) y los tipos de herramientas que pueden encontrar allí, así como el proceso para subir sus propias creaciones y materiales a la web de MIA y al repositorio.

A lo largo del curso destacamos la importancia del modelo de narración digital como un poderoso método para conectar con los estudiantes y como un recurso para hacer frente a los problemas actuales relacionados con el uso de los medios de comunicación. Destacamos la narración periodística como un método especialmente efectivo, debido a la naturaleza del entorno mediático actual, con temas como la desinformación, el clickbait, el astroturf, entre otros. Se especificaron diferentes métodos de manipulación de datos que afectan y confunden a la ciudadanía y a la opinión pública, formándoles así en su capacidad crítica.

Una de las principales limitaciones con las que nos encontramos fue la falta de conectividad y otras deficiencias tecnológicas en el centro. En una ocasión no pudimos acceder a Internet y en otra, los ordenadores portátiles no estaban completamente cargados y nos vimos obligados a replantearnos la parte final de la sesión debido a este problema. En lugar de desanimarnos, tomamos estas situaciones como oportunidades para la enseñanza, ya que los profesores se enfrentan a este tipo de problemas diariamente y hablamos sobre la importancia de tener siempre un plan de trabajo alternativo para nuestras clases. En nuestro caso, planificamos lecciones altamente tecnológicas pero también planes de respaldo en caso de no contar con esa tecnología.

Nos apoyamos en diferentes tipos de organizadores gráficos (para promover el pensamiento, la lluvia de ideas y las habilidades de planificación de nuestros participantes), incluyendo algunos específicos para desarrollar narrativas, como los guiones gráficos y la escaleta de podcasts, así como otros que conectan las técnicas de narración de historias con objetivos académicos específicos y técnicas de evaluación. También enviamos tareas a casa en los casos en que era importante tener un ordenador o acceso a Internet.

Utilizamos una variedad de aplicaciones móviles para alcanzar nuestros objetivos didácticos independientemente de la conectividad a Internet o la disponibilidad de ordenadores portátiles y, aunque nos encontramos con algunas limitaciones, como la baja memoria, la batería o una versión de software más antigua, el resultado fue muy satisfactorio. A medida que el programa del curso progresaba, nos comunicábamos con los profesores antes de la clase para descargar las aplicaciones requeridas y estábamos listos para empezar a trabajar con ellos al inicio de la misma.

Preveíamos los recursos en inglés como una limitación para nuestros educadores, pero pudimos abordar este problema al enseñarles a cómo utilizar Google Chrome para traducir automáticamente todos los sitios web. Como resultado, las sesiones en las que se utilizaron los recursos en inglés se desarrollaron a la perfección y fueron muy exitosas.

Los profesores eran proactivos y participaron activamente en cada actividad; en la mayoría de los casos trabajaban en grupos y adaptaban las actividades a sus alumnos y a su contexto. El interés de nuestros participantes en el aspecto instrumental del curso fue alto, pero evidenciamos un interés significativo en los temas de alfabetización mediática, especialmente los derechos de autor, las noticias falsas y la desinformación, la seguridad en línea y los prosumidores.

Creemos que la combinación de habilidades instrumentales de narración digital y el desarrollo de una conciencia en temas de alfabetización mediática fue fructífera y brindó una oportunidad para que se produjera un aprendizaje significativo. En muchos casos, los maestros conectaron lo que estaban aprendiendo con los programas que ya existían en sus escuelas y fueron capaces de mejorarlos y enriquecerlos añadiendo nuevos componentes a partir de nuestras lecciones.

Nos esforzamos por incluir materiales que fueran accesibles, gratuitos y fáciles de usar para cualquier profesor. También incluimos recursos adaptados a la materia y al contexto de cada uno de nuestros educadores; por ejemplo, tuvimos una profesora de matemáticas que pudo utilizar la narración digital en su aula utilizando una herramienta de Flipped Classroom y un vídeo de la plataforma TEDEd para enseñar a los alumnos cómo los gráficos y las estadísticas pueden ser engañosos. La acompañamos en cada paso del proceso y resolvimos todos sus problemas (por ejemplo, quería reducir la velocidad del video y le enseñamos cómo hacerlo) hasta que logró crear su lección incluyendo el video y un texto en hipervínculos que incluía otros contenidos.

Otro de nuestros participantes fue un profesor de formación profesional muy innovador que enseña salud en un programa de educación sanitaria. Actualmente está diseñando un proyecto gamificado de un año de duración basado en MasterChef para enseñar acerca de la nutrición, y utilizó varias de las herramientas que aprendió con nosotros para crear materiales únicos para sus estudiantes. El tema de las noticias falsas y la desinformación en el periodismo científico fue especialmente interesante para él y aportó importantes ejemplos de su tema y su contexto. Esto fue muy enriquecedor ya que otros participantes con menor competencia mediática evidenciaron que se trata de un tema que abarca todas las asignaturas. También nos enviará una actualización de su programa para el primer trimestre, que termina en diciembre.

Consideramos que tener el curso repartido en 4 semanas fue ventajoso porque el interés mostrado por varios de los profesores nos ofreció la oportunidad de adaptar el curso a sus necesidades y hacer un seguimiento de sus situaciones específicas. Al final evidenciamos un compromiso de todos ellos como educomunicadores con las herramientas necesarias para incluir estos temas en sus aulas. También se llevaron un conjunto de herramientas y habilidades instrumentales para ser implementadas en sus comunidades escolares.

MIA RECOMMENDATIONS

- Educator training in Media Literacy must be perceived as relevant. Educators need to see why the course is relevant to their practice as well as why they might need training in Media Literacy. By using digital storytelling and content creation as a vehicle through which to teach media literacy, the MIA approach has been successful in recruiting educators.

- Use a translation tool such as Google Chrome for web-based content. There are many English language resources which are useful in non-English speaking contexts, translation issues can be avoided by teaching educators to view resources in Chrome.

- Use accessible, free to use and creative commons licensed resources.

- Spreading the training over a long period or having chance to get to know your participants early on allows you to tailor the training to their requirements.

- Use technical problems as a teaching point and always have an ‘offline’ backup plan.

- Conference and event attendance builds and strengthens networks; maintaining a dialogue with new contacts can lead to new and useful resources being shared or created.

- Media literacy projects need to work together, collaboration means we have a greater impact.

- There should be a platform, a one-stop shop, which the EC could promote, to collate and signpost as much information and resources as is available in the area of media literacy.

Media in Action Glossary

Astroturfing: refers to the misleading practice of disguising the sponsors of a campaign, message or organization (which may be political, religious or commercial) to make them appear as a grassroots initiative. The name comes from the brand of artificial grass Astro Turf.

Algorithm: a mathematical set of rules to solve numerical problems, usually by a computer. Modern social media sites and search engines use complex algorithms to manage and manipulate the content available to users at any given time.

Blogs: website published on the Internet, consisting of diary-style text entries, posts. Blog also means to maintain or add content to a blog.

Clickbait: the practice of creating enticing hyperlinked headings that are often misleading, created with the sole purpose of attracting readers to an article or website.

Collaborative work: joint working, that covers a variety of forms that two or more organisations/persons/institutions can work together.

Community media: any form of media that is created and controlled by a community. It can be a geographic community or a community of identity or interest. Community media is different from commercial or public media.

Convergence Literacy: it is related with the convergence of multiple literacies to include technological, visual, digital and print, on and offline media proposals.

Convergence Culture: indicates a territory where old and new media cross each other, where grassroots and corporate media intersect, where the power of the media producer and the power of the consumer interact in the 21st century media system.

Digital Literacy: it is a part of media literacy. It refers to an individual’s ability to find, evaluate, produce and communicate information through forms of communication on various digital platforms.

Digital Storytelling: it is a practice of use digital tools to tell a story. Digital stories often present in compelling and emotionally engaging formats that can be interactive.

Disinformation: false information created to harm.

Fake News: refers to misleading content of a journalistic nature present on traditional and new media, created deliberately to deceive consumers of information and often to have an effect on public opinion.

Follower: term that refers to people who subscribe to a personal, professional or organizational profile on some media platforms. They receive the content of followed profiles directly in their personal wall and are able to interact with this content easily and often.

Hashtag: alphanumeric characters preceded by a hash sign to tag and classify content that belongs to a specific topic within some social media platforms.

Internet radio: a radio that is produced and broadcast with digital tools and through internet.

Journalistic Interview: this is a journalistic approach to finding out more about a topic, event or person. It involves a questionnaire and at least two participants: the interviewer often designs the questions and leads the exchange, the interviewee answers the questions and provides information.

Literacy: traditionally is the ability to read, write, spell, listen, and speak.

Media: collective communication outlets or tools used to store and deliver information or data, from traditional to new media.

Media hub: A device that directs multimedia content streamed from the Internet to a stereo or home system. Angela, please, revise a lot….

Media education: it is the process of and media literacy is the outcome. It is the ability to access, analyze, evaluate, and create media.

Media literacy: When people understand media and technology, they are able to access, analyze, evaluate, and create messages in a wide variety of media, genres, and forms.

Media literate: see media literacy.

Media skills:

Meme: content that usually includes a graphic (image, video or gif file) component and a textual component, it is commonly humorous and it is shared via the internet and modified by users.

Multimedia: the ability to use more than one medium of expression or communication.

News Literacy: it is a part of media literacy. Is the acquisition of critical-thinking skills for analyzing and judging the reliability of news and information, differentiating among facts, opinions and assertions in the media we consume, create and distribute.

Online radio: see Internet radio.

Open Badges: are digital indicators of skills. They can be used to recognise skills learned anywhere. They are not just a pretty picture, they contain rich metadata, coded into the badge image-file, such as who issued the badge and the criteria for awarding it.

Open Educational Resources: are teaching and learning resources which are freely available for anyone to use and repurpose providing the results are made available with the same conditions. They will usually have a creative commons license giving more information about how you can use them.

Participatory research: it is an approach to research in communities that gives importance participation and action. It seeks to understand the world by trying to change it, collaboratively and following reflection.

Podcast: it is an episodic series of digital audio or video files which a user can stream or download and listen to.

Self confidence: A positive belief in one’s self, which can be improved by performing and creating things successfully.

Social media: computer-mediated technologies that facilitate the creation and sharing of information, ideas, career interests and other forms of expression via virtual communities and networks.

Storyboard: sequenced graphics accompanied by text to plan and structure the progression of a story to be recorded in video format. It can be used for any project that includes video and audio.

Transmedia narratives: process of conveying messages, themes, or storylines through a sometimes strategic and sometimes organic use of multimedia platforms.

Transmedia storytelling: a process in which multiple stories set in a single universe (or storyworld) are told, using different media to tell diverse stories .

URL: the address of a website.

Vlogs: is a form of blog for which the medium is video and is a form of web television.

Wall: an element of some social media platforms that displays content from diverse sources: followed profiles, friends, advertising and news. What a user can see on their wall depends on the algorithm used by the said platform to optimize interactions and usage of the system.

Resources

Contacts

Ficha Técnica

Editors

- Angela Gerrard

- Maria José Brites

Contributions

- Angela Gerrard

- Inês Amaral

- Fernando Catarino

- Maria José Brites

Design

- Fernando Catarino

- Timóteo Rodrigues